On this page

Key information

|

Mode of transmission |

By inhalation of respiratory tract droplets or by direct contact with respiratory tract secretions. |

|---|---|

|

Incubation period |

Unknown, but probably 2–4 days. |

|

Period of communicability |

May be prolonged. Non-communicable within 24–48 hours after starting effective antimicrobial therapy. |

|

Burden of disease |

Children aged under 5 years, particularly those aged under 1 year: meningitis, epiglottitis, pneumonia and bacteraemia. |

|

Funded vaccines |

DTaP-IPV-HepB/Hib (Infanrix-hexa). Hib-PRP (Act-HIB). |

|

Dose, presentation, route |

DTaP-IPV-HepB/Hib and Hib-PRP:

|

|

Funded vaccine indications and schedule |

Usual childhood schedule:

For (re)vaccination of eligible patients:

For children <10 years receiving solid organ transplantation: up to 5 doses of DTaP-IPV-HepB/Hib. For testing for primary immune deficiencies: Hib-PRP. |

|

Vaccine effectiveness |

Hib disease has been almost eliminated in countries where Hib vaccine is used. |

|

Public health measures |

All cases of Hib disease be notified immediately on suspicion (see section 7.8). All child contacts should have their immunisation status assessed and updated as appropriate. |

|

Post exposure prophylaxis |

Antimicrobial prophylaxis should be administered to contacts as appropriate (see section 7.8). |

7.1. Bacteriology

Haemophilus influenzae is a gram-negative coccobacillus, which occurs in typeable and non-typeable (NTHi) forms. There are six antigenically distinct capsular types (a–f), of which type b is the most important. Before the introduction of the vaccine, H. influenzae type b (Hib) caused 95 percent of H. influenzae invasive disease in infants and children.

7.2. Clinical features

Transmission is by inhalation of respiratory tract droplets or by direct contact with respiratory tract secretions. Hib causes meningitis and other focal infections (such as pneumonia, septic arthritis and cellulitis) in children, primarily those aged under 2 years, while epiglottitis was more common in children over 2 years. Invasive Hib disease was rare over the age of 5 years, but could occur in adults. In the absence of vaccination these presentations may still occur. There have always been a small number of cases of H. influenzae invasive disease in adults, and these continue to occur. The incubation period of the disease is unknown, but is probably from two to four days.

Immunisation against Hib does not protect against infections due to other H. influenzae types or NTHi strains. Non-typeable H. influenzae (NTHi) organisms usually cause non-invasive mucosal infections, such as otitis media, sinusitis and bronchitis, but can occasionally cause bloodstream infection, especially in neonates. They are frequently present (60–90 percent) in the normal upper respiratory tract flora.

Young infants (aged under 2 years) do not produce an antibody response following Hib invasive disease, so a course of Hib-PRP vaccine is recommended when they have recovered (see section 7.5.3).

Hib and NTHi strains also cause diseases (including pneumonia and septicaemia) in the elderly.

7.3. Epidemiology

7.3.1. Global burden of disease

7.3.1. Global burden of disease

The source of the organism is the upper respiratory tract. Immunisation with a protein conjugate vaccine reduces the frequency of asymptomatic colonisation by Hib. Before the introduction of the vaccine, Hib was the most common cause of bacterial meningitis in children. Worldwide immunisation coverage is increasing, with approximately 194 countries having fully or partially introduced Hib onto their schedules by July 2019 (98 percent of all WHO member states).[1] The estimated global coverage for three doses of Hib is 72 percent as of July 2019.[2]

7.3.2. New Zealand epidemiology

7.3.2. New Zealand epidemiology

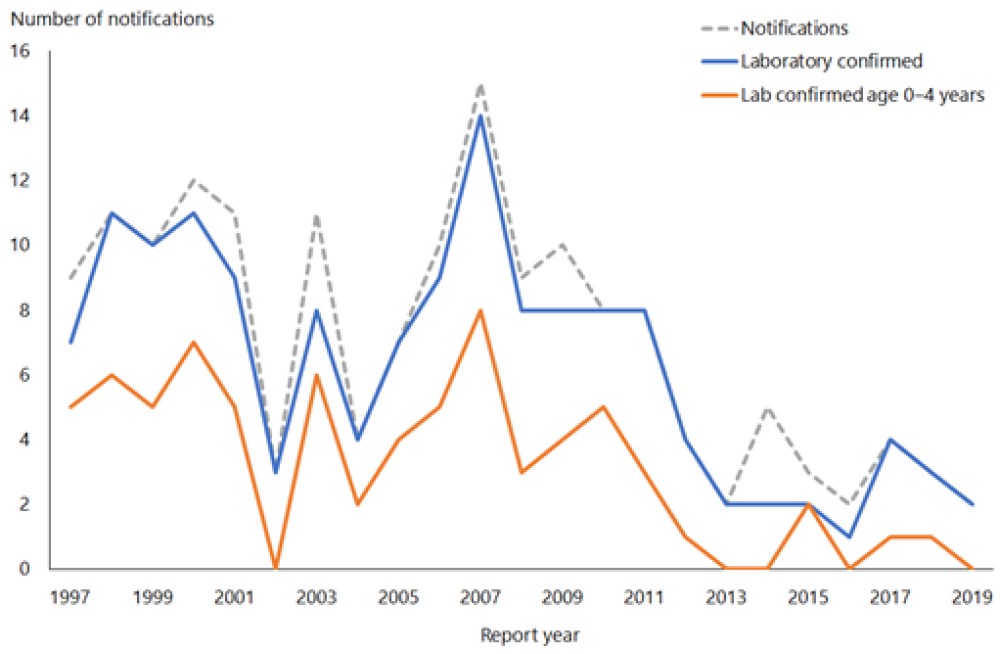

Hib-PRP was introduced in 1994 (see Appendix 1). In 1993, 101 children aged under 5 years had laboratory-confirmed invasive Hib disease (an age-specific rate of 36.4 per 100,000 population). By 1999 only five children in this age group had laboratory-confirmed disease (1.7 per 100,000) (Figure 7.1).

Two cases of Hib were notified and laboratory confirmed in 2019 (ESR, 8 June 2020). The cases were aged 50–59 and 60–69 years, both were unvaccinated. There were seven deaths from Hib between 1997 and 2019 (ESR, 8 June 2020), the most recent was in 2012 in an adult over 70 years of age.[3]

Figure 7.1: Number of notifications and culture-positive cases of Haemophilus influenzae type b invasive disease, 1997–2019

Source: ESR

For details of Hib notifications, refer to the most recent PHF Science (formerly ESR) notifiable disease annual tables and reports. (external link)

7.4. Vaccines

Antibodies to PRP, a component of the polysaccharide cell capsule of Hib, are protective against invasive Hib disease. To induce a T-cell dependent immune response, the polyribosylribitol phosphate (PRP) polysaccharide has been linked (conjugated) to a variety of protein carriers. These conjugate Hib vaccines are immunogenic and effective in young infants (see also section 1.4.3). The protein carriers used are either an outer membrane protein of Neisseria meningitidis (Hib‑PRP‑OMP vaccine), or a tetanus toxoid (Hib-PRP vaccine).

Note that the protein conjugates used in Hib vaccines are not themselves expected to be immunogenic and do not give protection against N. meningitidis or tetanus.

7.4.1. Available vaccines

7.4.1. Available vaccines

Funded vaccines

The Hib vaccines funded as part of the Schedule are:

- Hib-PRP, given as the hexavalent vaccine DTaP-IPV-HepB/Hib (Infanrix-hexa, GSK). It contains diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis, inactivated polio, hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine (see section 6.4 for more information)

- Hib-PRP given as monovalent Hib vaccine (Act-HIB, Sanofi). It contains 10 µg of purified Hib capsular PRP polysaccharide conjugated to 18-30 µg of tetanus protein. Other components (excipients) include trometamol and sucrose and sterile saline solution in the diluent.

Other vaccines

No other Hib vaccines are available currently. Hib-PRP (Hiberix, GSK) was the funded vaccine prior to October 2024.

7.4.2. Efficacy and effectiveness

7.4.2. Efficacy and effectiveness

The high efficacy and effectiveness of Hib-PRP vaccines have been clearly demonstrated by the virtual elimination of Hib in countries implementing the vaccine,[4, 5, 6] including New Zealand. Hib-PRP vaccines are highly effective after a primary course of two or three doses.[7, 8, 9] Disease following a full course of Hib-PRP is rare.

Conjugate vaccines reduce carriage in immunised children and as a result also decrease carriage and disease in unimmunised people (herd immunity). These vaccines will not protect against infection with NTHi strains, and therefore do not prevent the great majority of otitis media, recurrent upper respiratory tract infections, sinusitis or bronchitis.

(See also section 16.4.2 for information about the DTaP‑IPV‑HepB/Hib vaccine.)

Duration of immunity

A primary series followed by a booster dose in the second year of life should provide sufficient antibody levels to protect against invasive Hib disease to at least the age of 5 years.[10]

7.4.3. Transport, storage and handling

7.4.3. Transport, storage and handling

Transport according to the National Standards for Vaccine Storage and Transportation for Immunisation Providers 2017 (2nd edition).

Store at +2°C to +8°C. Do not freeze. DTaP-IPV-HepB/Hib should be stored in the dark.

DTaP-IPV-HepB/Hib vaccine (Infanrix-hexa) must be reconstituted by adding the entire contents of the pre-filled syringe containing DTaP‑IPV-HepB vaccine to the vial containing the Hib powder. After adding the vaccine to the powder, the mixture should be shaken until the powder is completely dissolved. Use the reconstituted vaccine as soon as possible. If storage is necessary, the reconstituted vaccine may be kept for up to eight hours at 21°C.

Monovalent Hib-PRP vaccine (Act-HIB) must be reconstituted with the supplied diluent and used immediately after reconstitution.

7.4.4. Dosage and administration

7.4.4. Dosage and administration

The dose of DTaP-IPV-HepB/Hib and Hib-PRP vaccines is 0.5 mL administered by intramuscular injection. Hib-PRP can also be administered subcutaneously if indicated (see section 2.2.3).

Co-administration

DTaP-IPV-HepB/Hib and Hib-PRP vaccines can be co-administered with other routine vaccines on the Schedule, in separate syringes and at separate sites.

7.5. Recommended immunisation schedule

7.5.1. Usual childhood schedule

7.5.1. Usual childhood schedule

Hib vaccine is funded for all children aged under 5 years. Three doses of DTaP-IPV-HepB/Hib (Infanrix-hexa) vaccine are given as the primary course, with a booster of monovalent Hib-PRP at age 15 months (see Table 7.1).

Table 7.1: Usual childhood Hib schedule (excluding catch-up)

|

Age |

Vaccine |

Comment |

|---|---|---|

|

6 weeks |

DTaP-IPV-HepB/Hib |

Primary series |

|

3 months |

DTaP-IPV-HepB/Hib |

Primary series |

|

5 months |

DTaP-IPV-HepB/Hib |

Primary series |

|

15 months |

Hib-PRP |

Booster |

For children aged under 5 years who, for whatever reason, have missed out on Hib vaccine in infancy, a catch-up schedule is recommended. The total number of doses of Hib vaccine required is determined by the age at which Hib immunisation commences. Where possible, the combined available vaccines should be used, but individual immunisation schedules based on the recommended national schedule may be required for children who have missed some immunisations (see Appendix 2).

7.5.2. Special groups

7.5.2. Special groups

Children

Because of an increased risk of infection, it is particularly important that the following groups of children, whatever their age, receive the Hib vaccine as early as possible (see also sections 4.2 and 4.2.5):

- children with anatomical or functional asplenia, or who are suffering from sickle cell disease (if possible, it is recommended that children be immunised prior to splenectomy)

- children with partial immunoglobulin deficiency, Hodgkin’s disease or following chemotherapy (note, however, that response to the vaccine in these children is likely to be suboptimal)

- children with nephrotic syndrome

- HIV-positive children.

Recommendations for Hib vaccine for older children and adults with asplenia

Although there is no strong evidence of an increased risk of invasive Hib disease in asplenic older children and adults, some authorities recommend Hib immunisation for these individuals.[11, 12] The Hib PRP-T vaccine has been shown to be immunogenic in adults.

- Monovalent Hib-PRP vaccine is funded for older children and adults pre- or post-splenectomy or with functional asplenia; one dose of vaccine is recommended (see also section 4.3.3) if childhood vaccine schedule is incomplete or unknown.

Note: Pneumococcal, meningococcal, influenza, varicella and pertussis-containing vaccines are also recommended for these individuals; see section 4.2.5 and the relevant disease chapters.

7.5.3. Children who have recovered from invasive Hib disease

7.5.3. Children who have recovered from invasive Hib disease

Children aged under 2 years with Hib disease do not reliably produce protective antibodies and need to receive a complete course of Hib-PRP. The number of doses required will depend on the age at which the first dose after the illness is given, ignoring any doses given before the illness (follow the age-appropriate catch-up schedules in Appendix 2).

Commence immunisation approximately four weeks after the onset of disease.

Any immunised child who develops Hib disease or who experiences recurrent episodes of Hib invasive disease requires immunological investigation by a paediatrician.

7.5.4. (Re)vaccination

7.5.4. (Re)vaccination

Hib-PRP-containing vaccines are funded for vaccination and revaccination of eligible patients, as follows. See also section 4.2.5.

DTaP-IPV-HepB/Hib (Infanrix-hexa)

Up to an additional four doses (as appropriate) of DTaP-IPV-HepB/Hib are funded for vaccination or revaccination of children aged under 10 years:

- post-HSCT or chemotherapy

- pre- or post-splenectomy

- pre- or post-solid organ transplant

- undergoing renal dialysis

- prior to planned or following other severely immunosuppressive regimens.

Up to an additional four doses (as appropriate) of DTaP-IPV-HepB/Hib are funded for children aged 10 years to under 18 years for (re)vaccination of patients post HSCT. This is an off-label use of this vaccine which requires a prescription from an authorised prescriber or the patient’s specialist. In this group, all prior immunity will have been lost and revaccination is equivalent to a primary immunisation schedule. DTaP-IPV-HepB/Hib not recommended for other severely immunocompromised individuals aged 10-18 years that require revaccination as they may have residual immune memory.

monovalent Hib-PRP

One additional dose of monovalent Hib-PRP is funded for vaccination or revaccination of patients:

- post-HSCT or chemotherapy

- pre- or post-splenectomy or with functional asplenia

- pre- or post-solid organ transplant

- pre- or post-cochlear implants

- undergoing renal dialysis

- prior to planned or after other severely immunosuppressive regimens.

7.5.5. Pregnancy and breastfeeding

7.5.5. Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Hib-PRP is not routinely recommended for pregnant or breastfeeding women. However, for women with asplenia see the ‘Recommendations for Hib vaccine for older children and adults with asplenia’ in section 7.5.2.

7.6. Contraindications and precautions

See also section 2.1.3 for pre-vaccination screening guidelines and section 2.1.4 for general vaccine contraindications. Anaphylaxis to a previous vaccine dose or any component of the vaccine is an absolute contraindication to further vaccination with that vaccine.

See section 16.6 for contraindications and precautions to DTaP‑IPV‑HepB/Hib vaccine.

Hib-PRP vaccines should not be administered to people with a history of an anaphylactic reaction to a prior dose of Hib vaccine or to a vaccine component. Significant hypersensitivity reactions to Hib vaccines appear to be extremely rare.

7.7. Potential responses and AEFIs

See section 16.7.1 for potential responses and AEFIs with DTaP‑IPV‑HepB/Hib vaccine.

7.7.1. Potential responses

7.7.1. Potential responses

Adverse reactions to Hib-PRP conjugate vaccines are uncommon. Pain, redness and swelling at the injection site occur in approximately 25 percent of recipients, but these symptoms typically are mild and last less than 24 hours.[13]

7.7.2. AEFIs

7.7.2. AEFIs

A meta-analysis of trials of Hib-PRP vaccination from 1990 to 1997 found that serious adverse events were rare.[14] No serious vaccine-related adverse experiences were observed during clinical trials of Hib vaccine alone. There have been rare reports, not proven to be causally related to Hib vaccine, of transverse myelitis, thrombocytopenia and Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS).[15]

7.8. Public health measures

It is a legal requirement that all cases of Hib disease be notified immediately on suspicion to the local medical officer of health, who will arrange for contact tracing, immunisation and administration of prophylactic rifampicin, where appropriate.

For detailed information see the Communicable Disease Control Manual.

7.8.1. Management of contacts

7.8.1. Management of contacts

All child contacts should have their immunisation status assessed and updated, as appropriate.

Immunisation reduces – but does not necessarily prevent – the acquisition and carriage of Hib. Therefore, immunised children still need antimicrobial prophylaxis, when indicated, to prevent them transmitting infection to their contacts. All contacts need to be assessed for the need for antimicrobial prophylaxis.

For further information, see the Communicable Disease Control Manual.

7.9. Variations from the vaccine data sheets

The Hib-PRP data sheet states that the vaccine is indicated for use in children aged up to 5 years. However, Health New Zealand recommends that all children and asplenic adults (see section 7.5.2) or those with specified immunocompromised conditions (see section 7.5.4) receive Hib-PRP vaccine.[11, 16] There are not expected to be any safety concerns in regard to use in older age groups.

See section 16.9 for variations from the DTaP-IPV-HepB/Hib (Infanrix‑hexa) data sheet.

References

References

References

- World Health Organization ,UNICEF. 2019 Progress and challenges with achieving universal immunisation coverage: 2018 WHO/UNICEF estimates of National Immunization Coverage. Monitoring and Surveillance Monitoring and Surveillance; 2019 [updated July 2019]; URL: https://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/who-immuniz.pdf?ua=1 (external link) [PDF]. (accessed 3 July 2020)

- World Health Organization ,UNICEF. 2019 Global and regional immunization profile. URL: https://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/data/gs_gloprofile.pdf?ua=1 (external link) [PDF]. (accessed 3 July 2020)

- Institute of Environmental Science and Research Ltd. 2013. Notifiable and Other Diseases in New Zealand: Annual Report 2012 (ed.), Porirua: Institute of Environmental Science and Research Ltd. URL: URL: https://surv.esr.cri.nz/PDF_surveillance/AnnualRpt/AnnualSurv/2012/2012AnnualSurvRpt.pdf (external link) (accessed 3 July 2020)

- Ladhani SN. Two decades of experience with the Haemophilus influenzae serotype b conjugate vaccine in the United Kingdom. Clinical Therapeutics, 2012. 34(2): p. 385–99.

- Bisgard KM, Kao A, Leake J, et al. Haemophilus influenzae invasive disease in the United States, 1994–1995: near disappearance of a vaccine-preventable childhood disease. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 1998. 4(2): p. 229–37.

- MacNeil JR, Cohn AC, Farley M, et al. Current epidemiology and trends in invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease – United States, 1989–2008. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2011. 53(12): p. 1230–6.

- Griffiths UK, Clark A, Gessner B, et al. Dose-specific efficacy of Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Epidemiology and Infection, 2012. 140(8): p. 1343–55.

- O’Loughlin RE, Edmond K, Mangtani P, et al. Methodology and measurement of the effectiveness of Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine: systematic review. Vaccine, 2010. 28(38): p. 6128–36.

- Kalies H, Grote V, Siedler A, et al. Effectiveness of hexavalent vaccines against invasive Haemophilus influenzae type b disease: Germany’s experience after 5 years of licensure. Vaccine, 2008. 26(20): p. 2545–52.

- Khatami A, Snape MD, John TM, et al. Persistence of immunity following a booster dose of Haemophilus influenzae type B-meningococcal serogroup C glycoconjugate vaccine: follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 2011. 30(3): p. 197–202.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014. Prevention and control of Haemophilus influenzae type b disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Recommendations and Reports. 63(RR-1): p. 1–14. URL: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr6301.pdf (external link) (accessed 3 July 2020)

- Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI). 2018. Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib). in Australian Immunisation Handbook. Canberra. URL: https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au/vaccine-preventable-diseases/haemophilus-influenzae-type-b-hib (external link). (accessed 6 July 2020)

- American Academy of Pediatrics. 2018. Haemophilus influenzae infections. in Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, Kimberlin D, Brady M, Jackson M, et al. (eds). URL: https://redbook.solutions.aap.org/redbook.aspx (external link). (accessed 3 July 2020)

- Obonyo CO, Lau J. Efficacy of Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccination of children: a meta-analysis. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 2006. 25(2): p. 90–97.

- Nanduri S, Sutherland A, Gordon L, et al. 2018. Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccines, in Plotkin's Vaccines (7th edition), Plotkin S, Orenstein W, Offit P, et al. (eds). Elsevier: Philadelphia, US.

- Public Health England. 2016. Immunisation of individuals with underlying medical conditions. in The Green Book. URL: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/566853/Green_Book_Chapter7.pdf (external link). (accessed 1 April 2017)